Categories

Processes: Limited Direct Execution

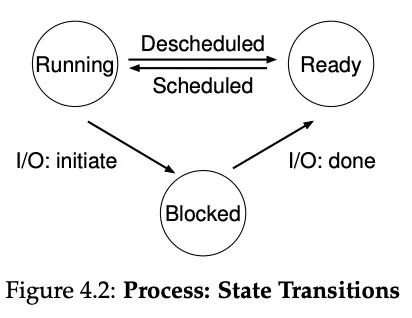

Direct Execution: to be as performant as possible, processes are run directly on the CPU.

If there were no limits though, how can the OS make sure the program doesn’t do anything we don’t want it to do? And how does the OS stop it from running to implement time sharing (required to virtualize the CPU).

1) Restricting Operations

A processor can be in:

- user mode: in this mode a process cannot issue I/O requests, if it did the OS would kill the process.

- kernel mode: in this mode the code can do whatever it wants.

System calls are OS-provided APIs that allow user programs to access key pieces of functionality exposed by the kernel.

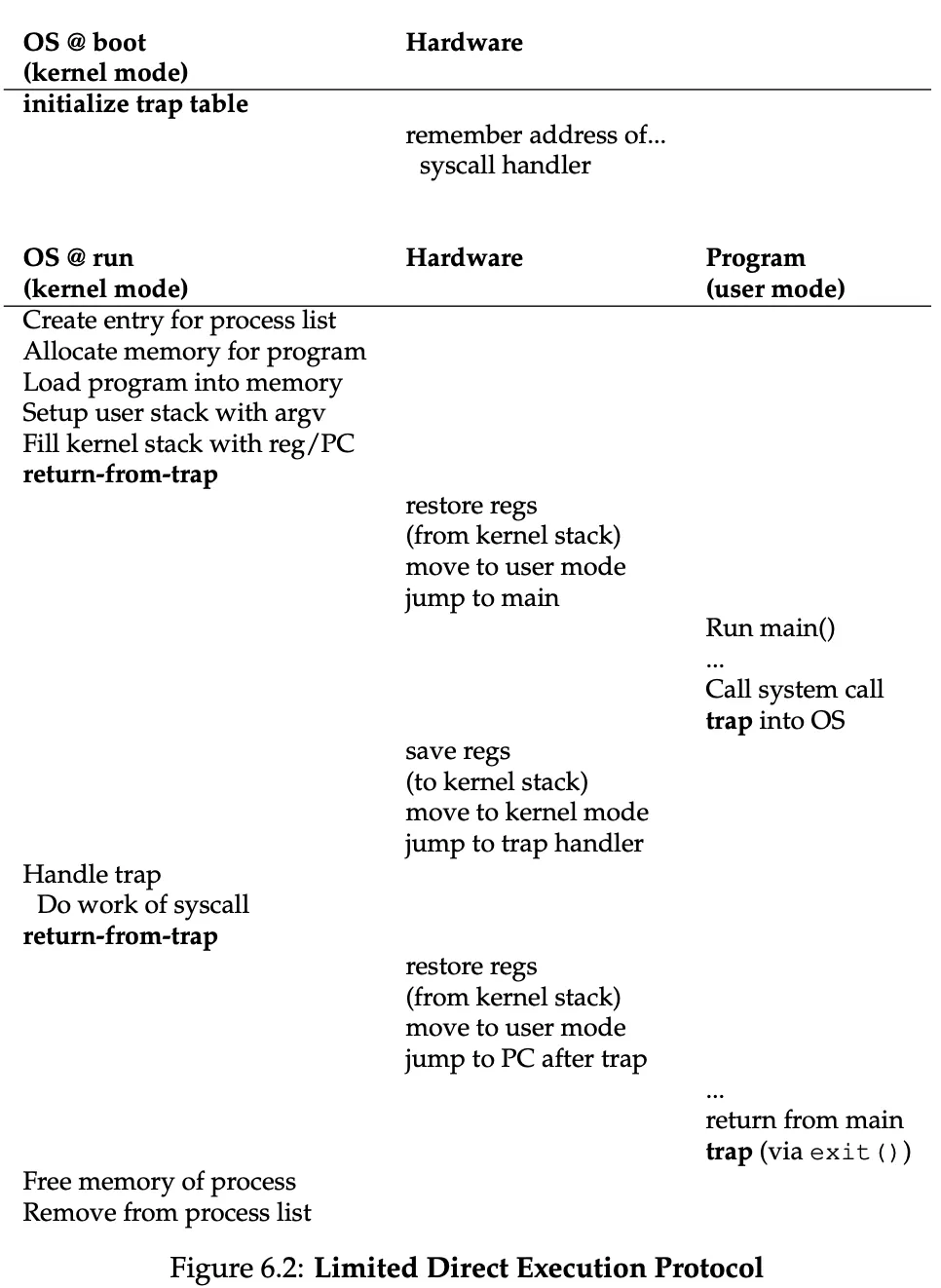

To execute a system call, a program must execute a trap instruction. This jumps into the kernel and raises the privilege level to kernel mode. When finishes, the OS calls a special return-from-trap instruction which returns into the calling user program while reducing privileges to user mode.

How does the trap know which code to run inside the OS?

At boot time, the kernel sets up a trap table. A table that specifies the memory addresses of trap handlers (what code to run when a harddisk interrupt takes place, etc. etc).

(when we talk about the memory stack, we refer to the user stack. kernel stack is in a different location, with different access permissions only used by the hardware and kernel to deal with traps/return-from-traps)

For added protection, when the user wants to execute a system call, it only places a system-call number in a register. Then the OS examines the number and ensures it’s valid, then executes the corresponding code.

2) Switching between processes

How does the OS regain control of the CPU? If the program is running, then the OS is not running…

- Cooperative approach: just wait for a system call. The OS trusts the processes of the system to behave reasonably. Remember programs often transfer control to the OS when I/O happens, or the program divides by zero or tries to access memory it shouldn’t access.

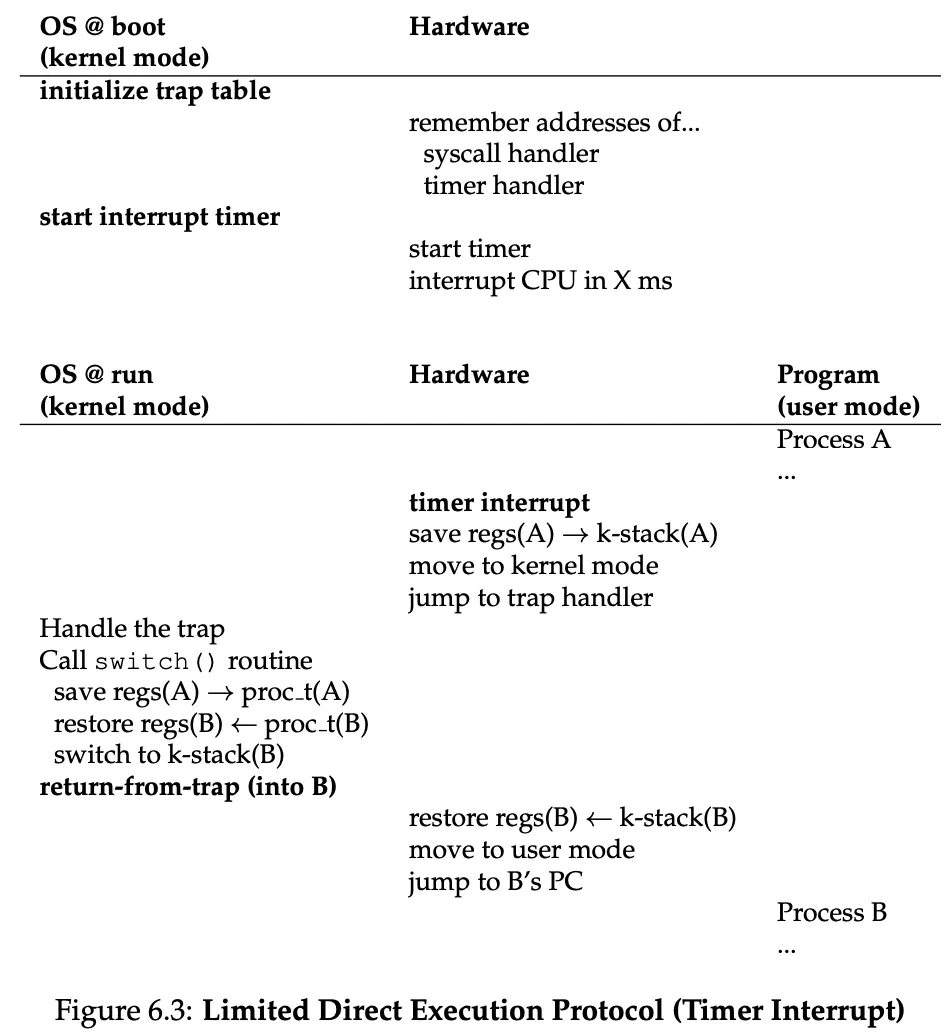

- Non-cooperative approach: we use a timer interrupt. A timer device is configured to raise an interrupt every so many milliseconds. At that point, a pre-configured interrupt handler in the OS runs. This timer is configured and started by the OS in privileged mode at boot time.

After the OS has regained control, it can choose to give the CPU to another process. This action is called context switching. This consists of saving a few register values for the current process on the kernel stack and popping a few for the next one to execute.

This is all done by some low-level assembly code.

Remember the process table contains a PCB for each process.

The kernel stack is switched as part of the context switch, because all kernel stacks are stored in the kernel memory.

Since the user stack is part of the process’s address space, that’s automatically handled when returning to user mode.

Everything that happens in kernel mode is stored on the kernel stack (local variables, function call frames, context information like registers, etc).

Everything that happens in user mode is stored on the user stack.

CPU Scheduling

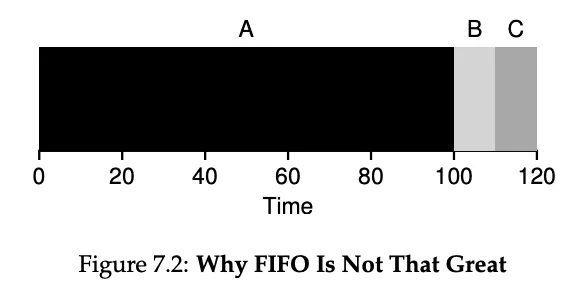

First In, First Out or First Come First Served

![]()

The convoy effect ^

Where a number of relatively-short potential consumers of a resource get queued behind a heavyweight resource consumer.

The average turnaround time can be pretty bad if the first job takes too long.

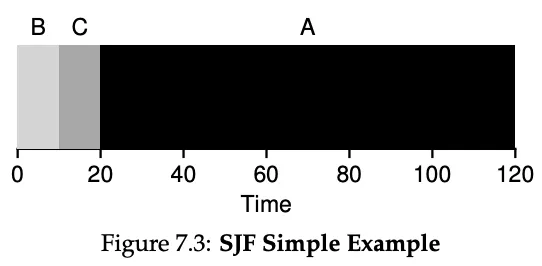

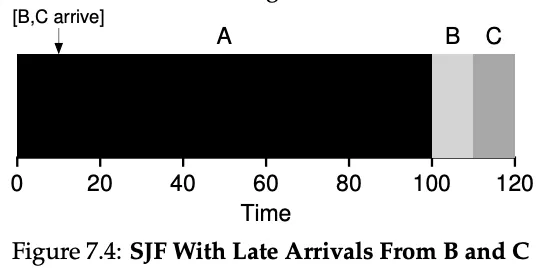

Shortest Job First

![]()

Fixes convoy effect.

![]()

Bad turnaround time.

It doesn’t work well if the scheduler is non-preemptive.

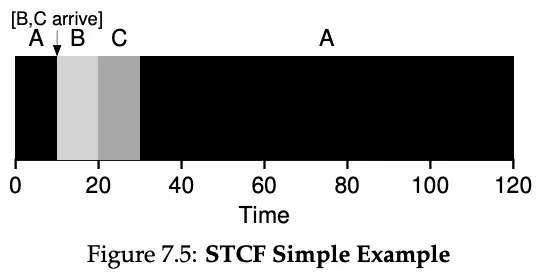

Shortest Time-to-Completion First (STCF)

This is just preemptive SJF.

![]()

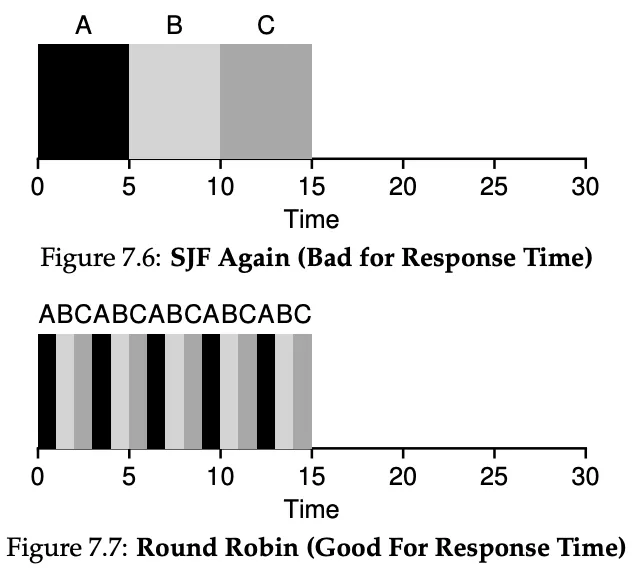

Round Robin

Unfortunately though… Computers need to be interactive. Using STCF, it could be that a longer process never gets its share of the CPU because there are always shorter jobs.

Response time = T_firstrun - T_arrival

But good for turnaround time.

But bad for turnaround time.

Therefore, we use Round Robin, which runs a job for a time slice or scheduling quantum.

Of course, the time slice cannot be too short, or the CPU will spend too much time context switching. It cannot be too high, or jobs starve.

Any policy that’s fair, like RR, will perform poorly on turnaround time.

Tradeoff: If you’re willing to be unfair, you can run shorter jobs to completion, but at the cost of response time. If you instead value fairness, response time is lowered, but at the cost of turnaround time.

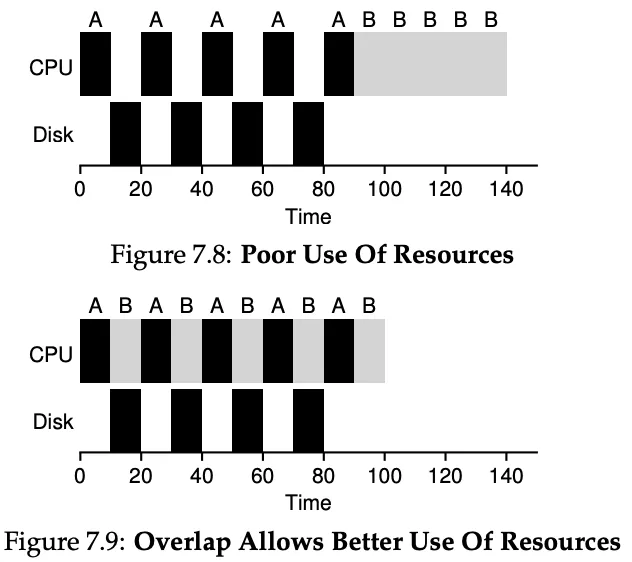

Incorporating I/O & No More Oracle

So far, we had assumed there was no I/O and that we knew from the beginning the length of each job. Unfortunately, these aren’t true.

The Multi-Level Feedback Queue

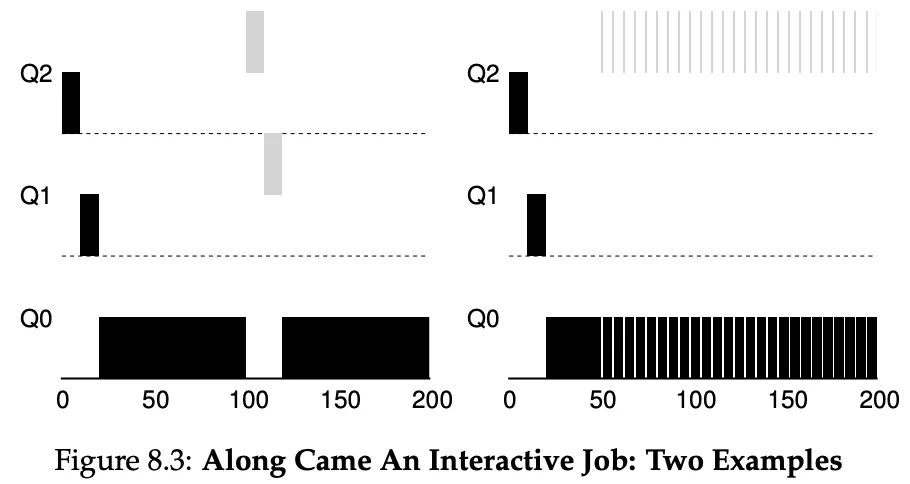

How do we optimize turnaround time (by running the shortest jobs first) when the OS doesn’t know the length of each job? And how do we make the system feel responsive to interactive users by minimizing response time?

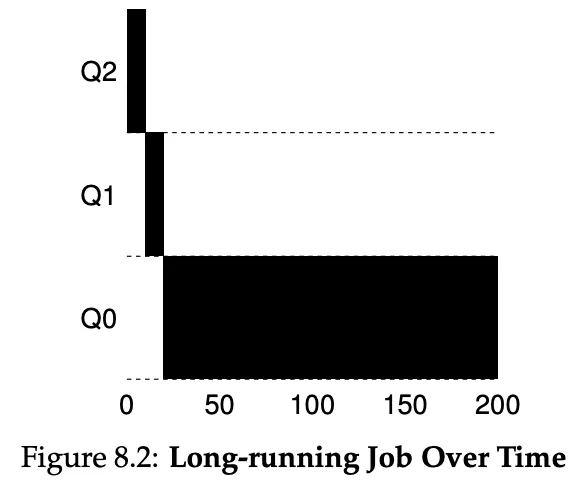

MLFQ varies the priority of a job based on its observed behavior. If a job frequently relinquishes the CPU (maybe to wait for input from the keyboard), the scheduler will keep its priority high.

Instead, if the job uses the CPU intensively for long periods of time, MLFQ will reduce its priority.

The rules for MLFQ:

-

If Priority(A) > Priority(B), A runs and B doesn’t.

-

If Priority(A) = Priority(B), A & B run in RR.

-

When a job enters the system, it is placed at the highest priority.

-

- If a job uses up its allotment while running, its priority is reduced.

- If a job gives up the CPU before allotment is up, it stays at the same priority level.

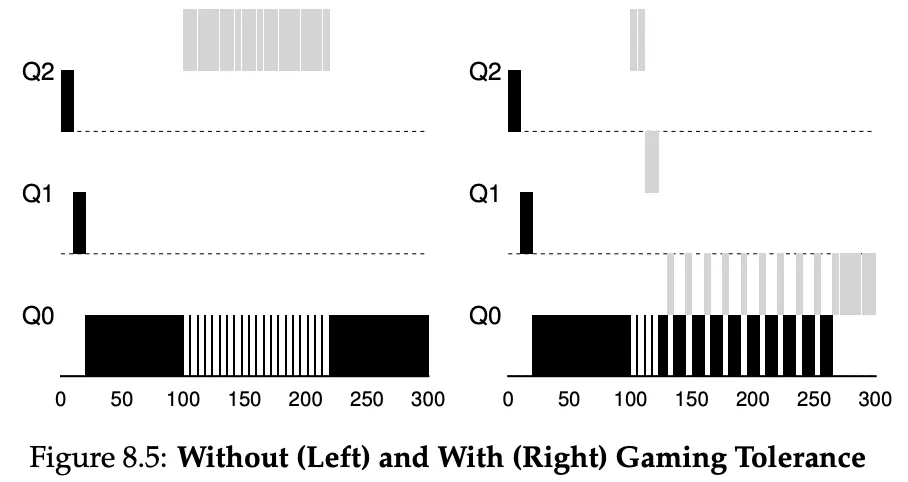

With the above rules, a user could game the scheduler. For example, a process could issue an I/O operation before its allotment is used, just to stay in the same queue.

- Once a job uses its time allotment at a given level (regardless of how many times it has given up the CPU), its priority is reduced (i.e., it moves down one queue).

-

After some time period in S, move all the jobs in the system to the topmost queue.

This was introduced to fix these problems:

- Starvation. If there are too many interactive jobs, the long-running ones will never run.

- If a long-running job becomes interactive, it will never have the same priority as the other ones.

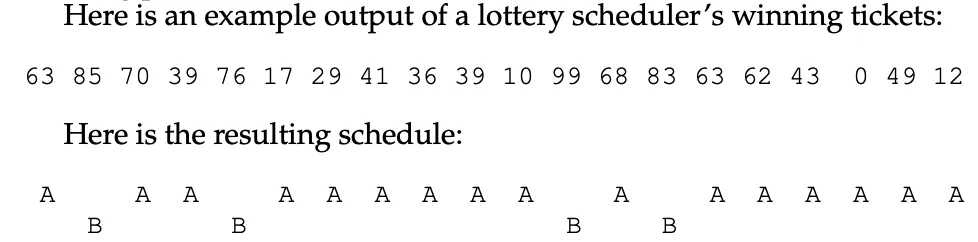

Proportional Share / Lottery Scheduling

These schedulers, instead of optimizing for response time or turnaround time, try to guarantee that each job obtains a certain percentage of CPU time.

Example with A having 75 tickets and B having 25.

Each job holds a number of tickets, and then the schedulers generate a random number from 0 to the total number of tickets. It then picks the closest job whose percentage is after the random number.

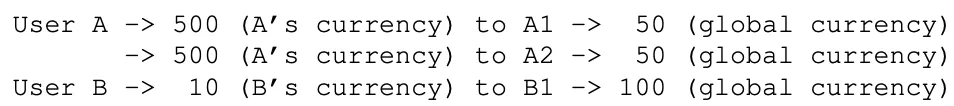

We have a number of mechanisms to manipulate tickets in interesting ways.

Your job wants to spawn other processes, each with its own tickets and currency? You can!

A process can also temporarily hand off its ticket to another process. Maybe when a client asks a server to do some work on its behalf. To speed up the server’s performance, the client can send its tickets.

Ticket inflation is a thing. A process can temporarily raise or lower the number of tickets it owns. This can be done in a system where processes trust one another, and it’s not competitive.

Linux Completely Fair Scheduler (CFS)

The scheduler efficiency is really important. It has to spend little time making decisions.

The basic idea is this: every job, as it runs, accumulates vruntime. The scheduler, will pick the process with the lowest vruntime to run next.

How does the scheduler know when to stop the current process?

CFS manages this through various control parameters.

- sched_latency. How long a process shoudl run before considering a switch. Typical value is 48ms. CFS divides this by number of processes to determine the time slice for each process.

- min_granularity. What if there’s more than 48 processes? The OS will never set the time slice lower than the min_granularity, usually 6ms.

- niceness. admins can give higher priority to the CPU to some processes by confuring the nice level of a process. from -20 to +19. 0 being default. -20 being higher priority. (yes)

The CFS keeps running processes in a red-black tree. if it goes to sleep or it’s blocked, it’s removed.

Multiprocessor Scheduling

(advanced chapter to do later)