Categories

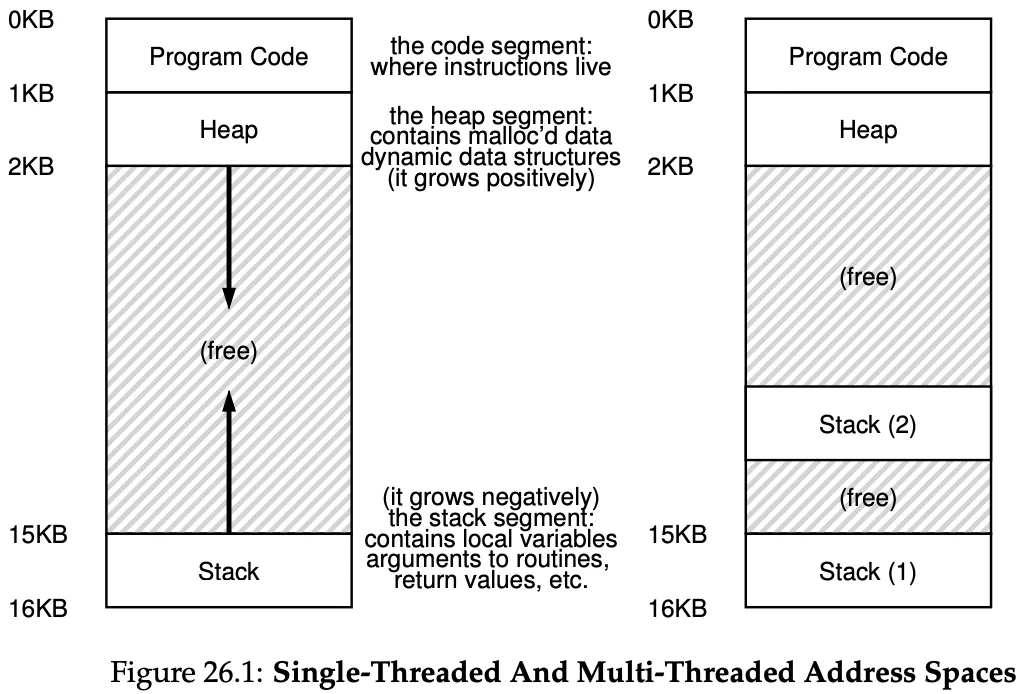

A multithreaded program has multiple PCs, each of which is being fetched and executed from.

Threads are similar to separate processes.

Similarities with processes:

- each thread has a program counter (PC) that tracks where the program is fetching instructions from

- each thread has its own set of registers it uses for computation

- therefore, it two threads run on a single processor, when switching from running one thread to another, a context switch has to take place

Differences with processes:

-

threads share the same address space and thus can access the same data.

-

the context switch that happens whens switching from one thread to another:

- register state of old thread must be savde and the register state of new thread must be restored

- instead of saving state to PCB, we save to TCBs (Thread Control Blocks), for state of each thread of the process

- NO NEED to switch which page table we’re using. as threads use the same address space.

-

we have 1 stack per thread. obviously because each thread runs independently and may call into various routines

The above address space is less beautiful but normally ok, as stacks do not have to be very large.

Why use Threads?

- Parellelism: make programs run faster by using a thread per CPU (let’s say incremeneting the value of each element in a very large array)

- Avoiding blocking program due to I/O: when an I/O has to happen, you can use one thread to dispatch it and make it wait, and other threads which are ready to run and do something useful.

- Threading enables the overlap of I/O with other activities within a single program

- Exactly like multiprogramming does, for processes across programs

You could use processes too, but threads share an address space and thus make it easy to share data (context switching is also slightly faster). Processes make more sense for logically separate tasks where little sharing of data structures in memory is needed.

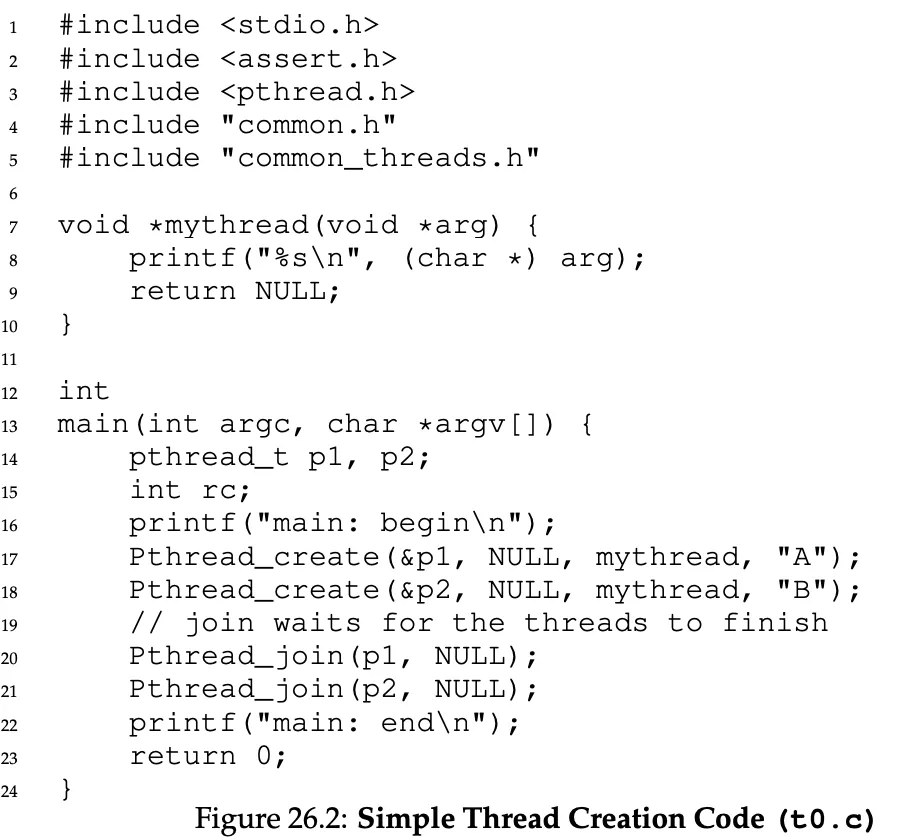

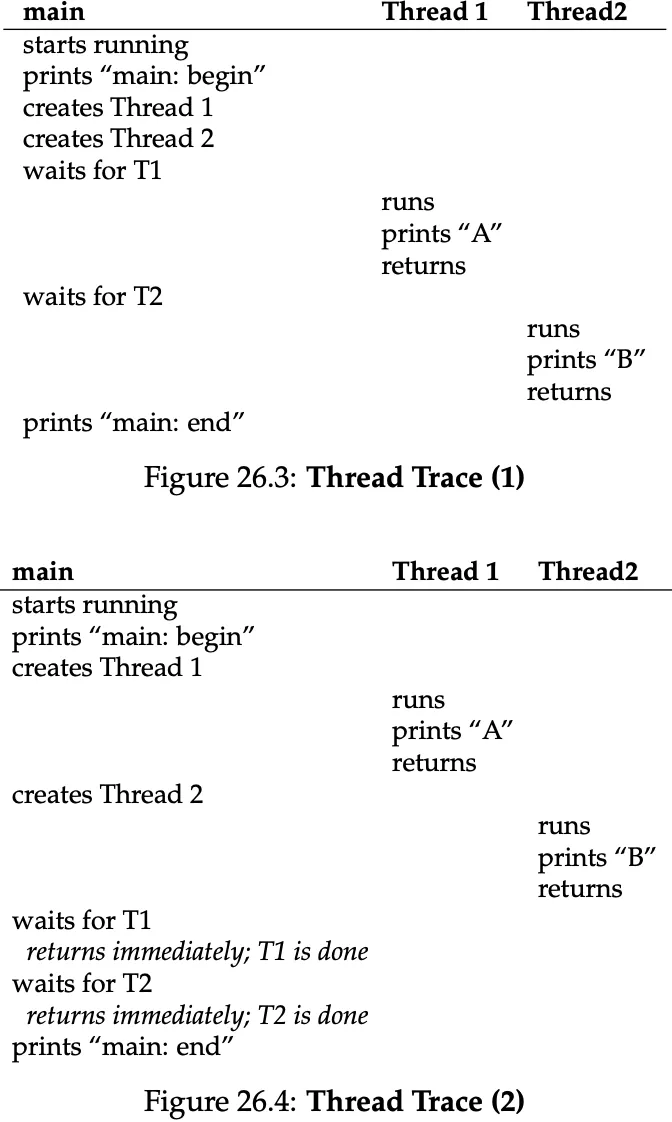

Simple Thread Example

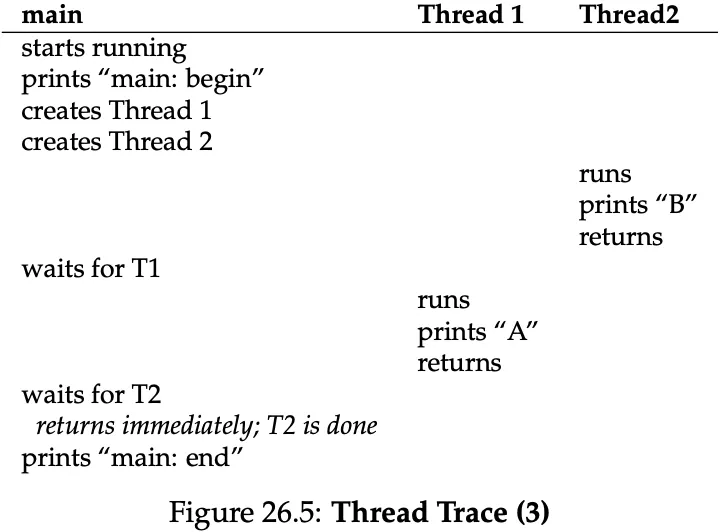

as you can see from the right, there multiple possible thread traces, depending on when the OS scheduler decides to run each thread.

Shared Data

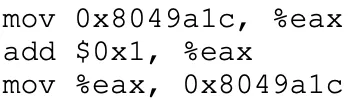

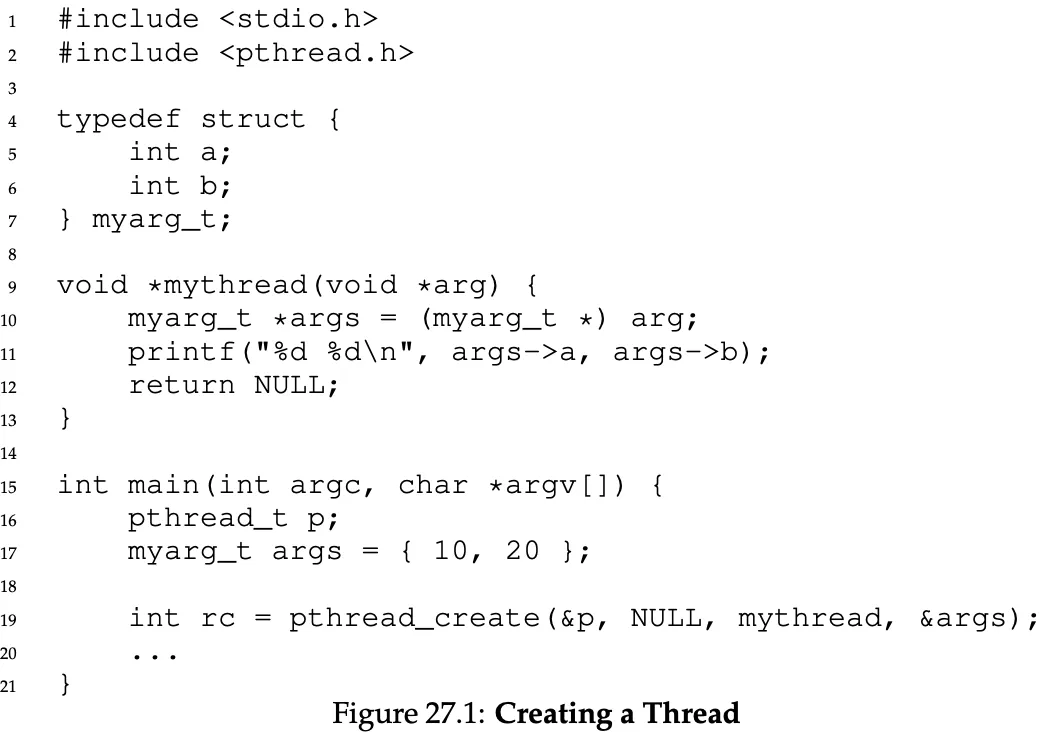

If two threads try to add 1 million to a counter (naively), we might expect the final count to be 2 millions. Actually this doesn’t work, because counter++ is not atomic.

This is what happens when counter++ runs:

A timer interrupt could be dispatched while T1 is in this block of code, the OS saves the state of T1 (its PC, its registers, including eax , etc, to T1’s TCB), and then T2 runs. This could yield unexpected results.

This code is called a critical section, because it can result in race conditions (where results depend on the timing of the code’s execution).

A critical section is a piece of code that accesses a shared resource and must not be concurrently executed by more than one thread.

We solve this with mutual exclusion → if T1 is executing the critical section, others will be prevented from doing so.

The Wish For Atomicity

We would like to turn that 3 assembly instructions into a single atomic instruction.

The hardware will need to provide us with some instructions we can use to build a set of synchronization primitives.

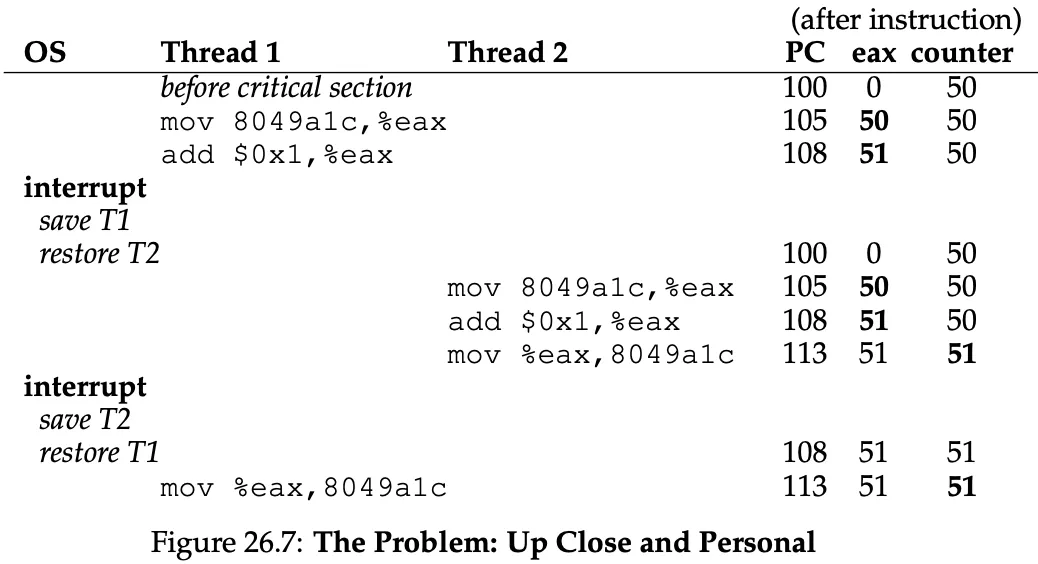

Creating a thread

int pthread_create(pthread_t *thread, const pthread_attr_t *attr, void *(*start_routine)(void*), void *arg);

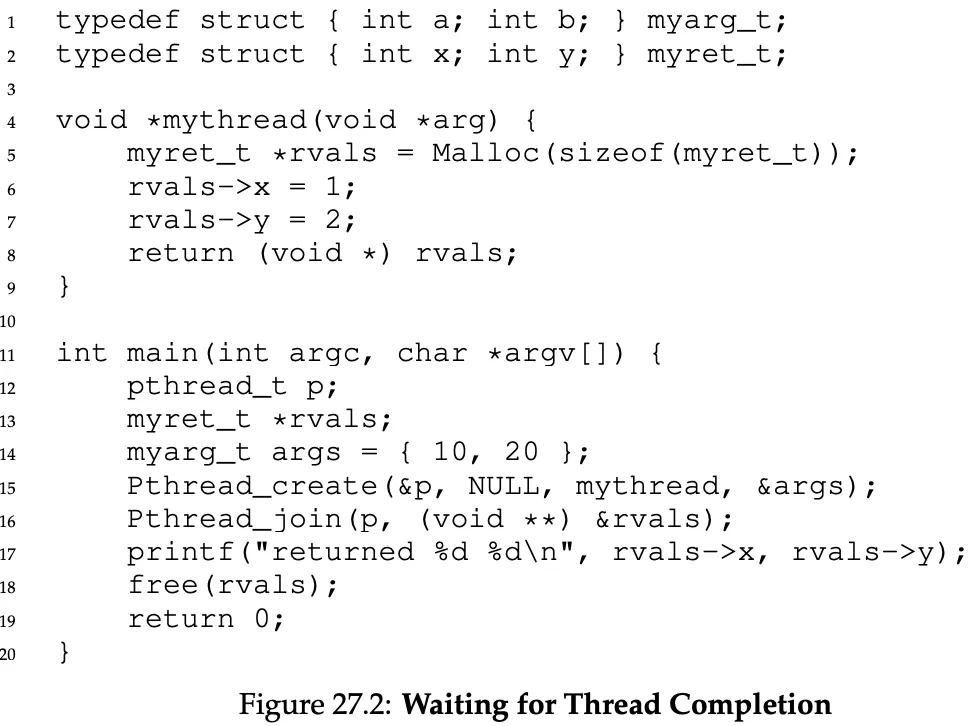

Waiting for thread completion

pthread_join() takes in a double pointer to the return value, because it can modify the existing pointer (ofc, it needs to put the return value inside).

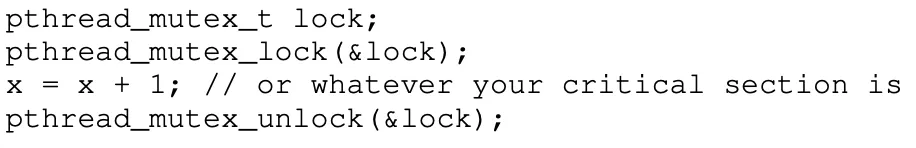

Locks

lock function is blocking, thread waits until it can grab the lock.

btw lock has to be initialized statically: pthread_mutex_t lock = PTHREAD_MUTEX_INITIALIZER;

or dynamically: int rc = pthread_mutex_init(&lock, NULL);

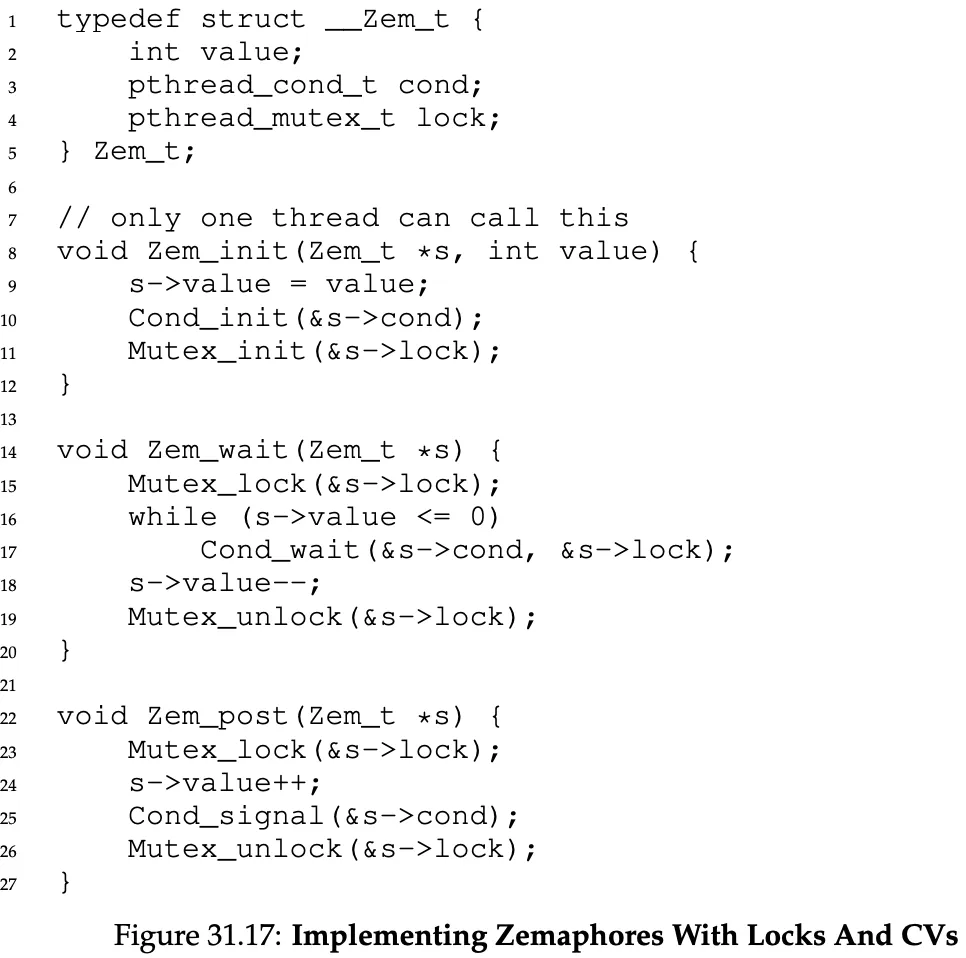

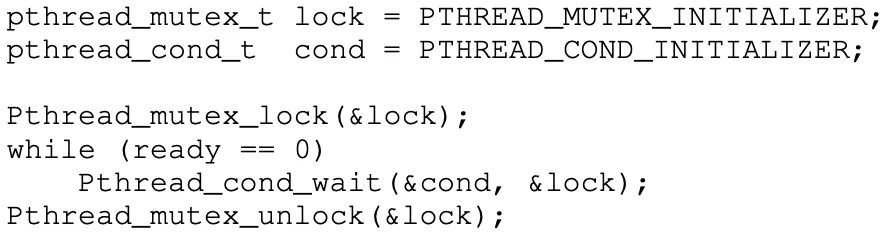

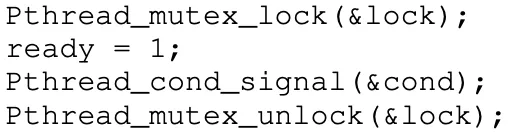

Condition Variables

These are used when some kind of signaling has to take place among threads (one thread is waiting for another to do something before it can continue).

int pthread_cond_wait(pthread_cond_t *cond, pthread_mutex_t *mutex); → puts the calling thread to sleep until it’s signaled by int pthread_cond_signal(pthread_cond_t *cond);

Use a while loop instead of an if. The thread could be awaken at random, and think ready = 1 when it’s not.

Why does pthread_cond_wait() take in the lock? because while waiting, the lock is released, of course. otherwise, the other thread wouldnt be able to acquire it. However, just before it’s awaken, it grabs the lock again.

Why are we using locks and condition variables at the same time? Well, ready is a shared resource, we wouldn’t want a race condition.

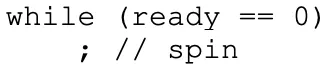

Why use condition variables instead of waiting just like this?

^^^ BAD BAD BAD ^^^ → it wastes CPU cycles instead of being blocked, and it’s error prone.

Tips:

- Keep it simple

- Minimize thread interactions

- Initialize locks and condition variables

- Check your return codes (in any C and Unix programming you do!)

- Be careful with how you pass args or return vals from threads. If you pass a reference to a stack-allocated variable, you’re stupid.

- Each thread has its own stack, remember! To share data between threads, they have to be in the heap (or some locale that is globally accessible).

- Always use condition variables to signal between threads. Don’t use a simple flag!!!

Locks Implementation

Criteria for a good lock:

- Does it provide mutual exclusion?

- Is it fair? (does each thread contending for the lock get a fair shot at acquiring it once it’s free?)

- Is performant? (how much overhead does it add?)

How to implement

Controlling Interrupts

If we were on a single processor, one way would be to disable interrupts when acquiring the code, and enabling them when releasing it.

Ofc this solution is bad, we’re trusting applications too much. Doesnt work on multiprocessors too. Also, if we disable interrupts for too long the OS might miss the fact that some I/O operations finished.

This could be nonetheless used by the OS itself for some of its own data structures.

Why just using load / store doesnt work

If we just use a simple integer variable, two problems arise:

- Correctness: both threads could set the flag to 1 at the same time

- Performance: if threads wait using a while loop, they will be spin-waiting therefore just wasting cpu cycles.

The Test-And-Set (or atomic exchange) instruction

This type of lock provides mutual exclusion, but not fairness or performance (both due to spin-waiting). Also this requires the scheduler to be preemeptive. If yu spin lock on a non-preemptive shceduler the thread will never relinquish the CPU.

Compare-And-Swap (or Compare-And-Exchange)

Checks the value of a variable and if it’s the expected value, atomically sets to another value.

Fetch-And-Add

One hardware instruction to fetch to increment a value and return the old value. Very powerful.

With this you can implement ticket locking (increment a counter and when that counter is equal to a thread’s ticket then it’s their turn) and that ensures fairness too.

How to ensure performance (no spin locking)

Yield! Whenever you cannot grab a lock, yield, so you give up the CPU (moving your state from running to ready).

This is beter than spin locking but it’s still not optimal, here’s why:

- assume we have a round robin scheduler with 100 thread. if 1 thread holds the lock, and is preempted, then the other 99 threads will try to lock() and then yield again. a lot of context switching.

- doesn’t address starvation. a thread may get caught in an endless yield loop.

Queues

Basically, a queue of threads, when unlocking a thread calls the next thread in the queue to wake up. When locking, the thread puts himself in the queue if it cant acquire the lock.

Two-Phase Locks

How about this: if a lock cant be grabbed, the thread spins for a while hoping to acquire it. if it can’t grab it, in the second phase, it’s put to sleep until the lock becomes free later. → hybrid approach

Lock-based Concurrent Data Structures

There’s countes, linked lists, queues and hashmaps with locking built-in so they’re concurrent.

Condition Variables

What if you want to check if a condition is true before continuing your execution? And of course you dont want to check a shared variable while spinning (wasting CPU cycles).

A condition variable is a queue that threads can put themselves on when waiting for some condition. Some other thread, when it changes said state, can then wake one or more waiting threads (signaling).

pthread_cond_wait(pthread_cond_t *c, pthread_mutex_t *m);

release the lock, put calling thread to sleep. after waking up, it will re-acquire the lock.

pthread_cond_signal(pthread_cond_t *c);

signal another thread to wake up.

do you need a lock when waiting on a condition variable? yes you do.

and do you need the lock when signaling? not always but most likely yes.

why? let’s say you check if done == 0 , it is, so you want to go sleep, but right before you go sleep, the other thread changes done = 1 and signal() you to awake. but you’re not even asleep yet, you were just going to! so when you get the CPU back, you go to sleep and will never be awaken again. sad death.

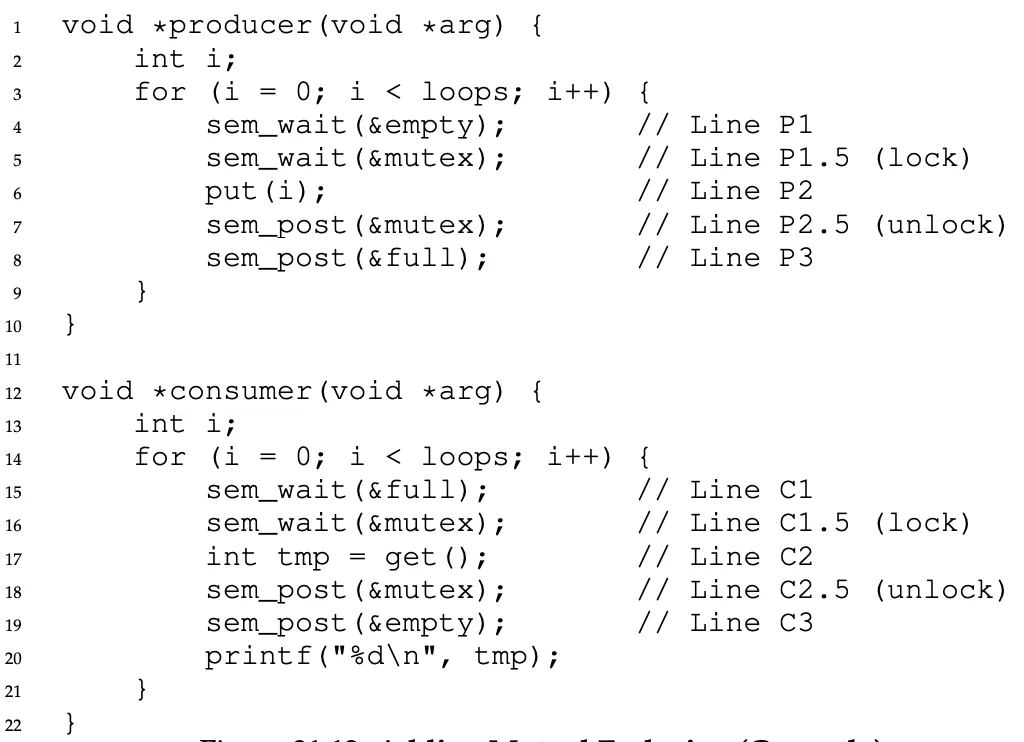

Producer/Consumer problem (or bounded buffer)

To work on a proper bounded buffer, you need both a lock (to actually check shared resource) and a condition variable (to check that the buffer is empty - for the producer - and the buffer is full - for the consumer).

For a proper working solution, you need two condition variables, not just one.

If you use one, and you have two consumers, after a thread consumes from the buffer, it will signal the queue. But in the queue there can be both producer and the second consumer. If the second consumer wakes up, sees the buffer is empty, goes back to sleep, all three threads will be left sleeping for ever.

Consumers should not wake other consumers, only producers. And vice-versa.

Therefore:

- Producer threads wait on the condition empty, and signal fill

- Consumer threads wait on fill and signal empty

By doing this, a consumer can never accidentally wake a consumer, and a producer can never accidentally wake a producer.

Semaphores

Semaphores allows us to replace locks and condition variables.

A semaphore is an object with an integer value that we can manipulate with:

- sem_wait → decrement value by one, wait if value is negative

- sem_post → increment value by one, if threads waiting, wake one

When the value of the semaphore is negative, it will equal the number of waiting threads (useful to know).

You can use a binary semaphore as a lock (value can be [-1, 1]):

- -1: a thread is waiting, lock in use

- 0: no threads waiting, lock in use

- 1: no threads waiting, lock not in use

On Linux semaphores can never be negative. The implementation above is the one done by Djikstra though.

Semaphores can also be used for ordering, and for solving the producer consumer problem.

why do you need a mutex lock too? 3 semaphores??

yes. what if you have 2 producers, that at the same time put a value in the queue, but the first producer is interrupted just before it manages to increase the counter of elements inside. the second producer will overwrite the first element!!!!!!!!

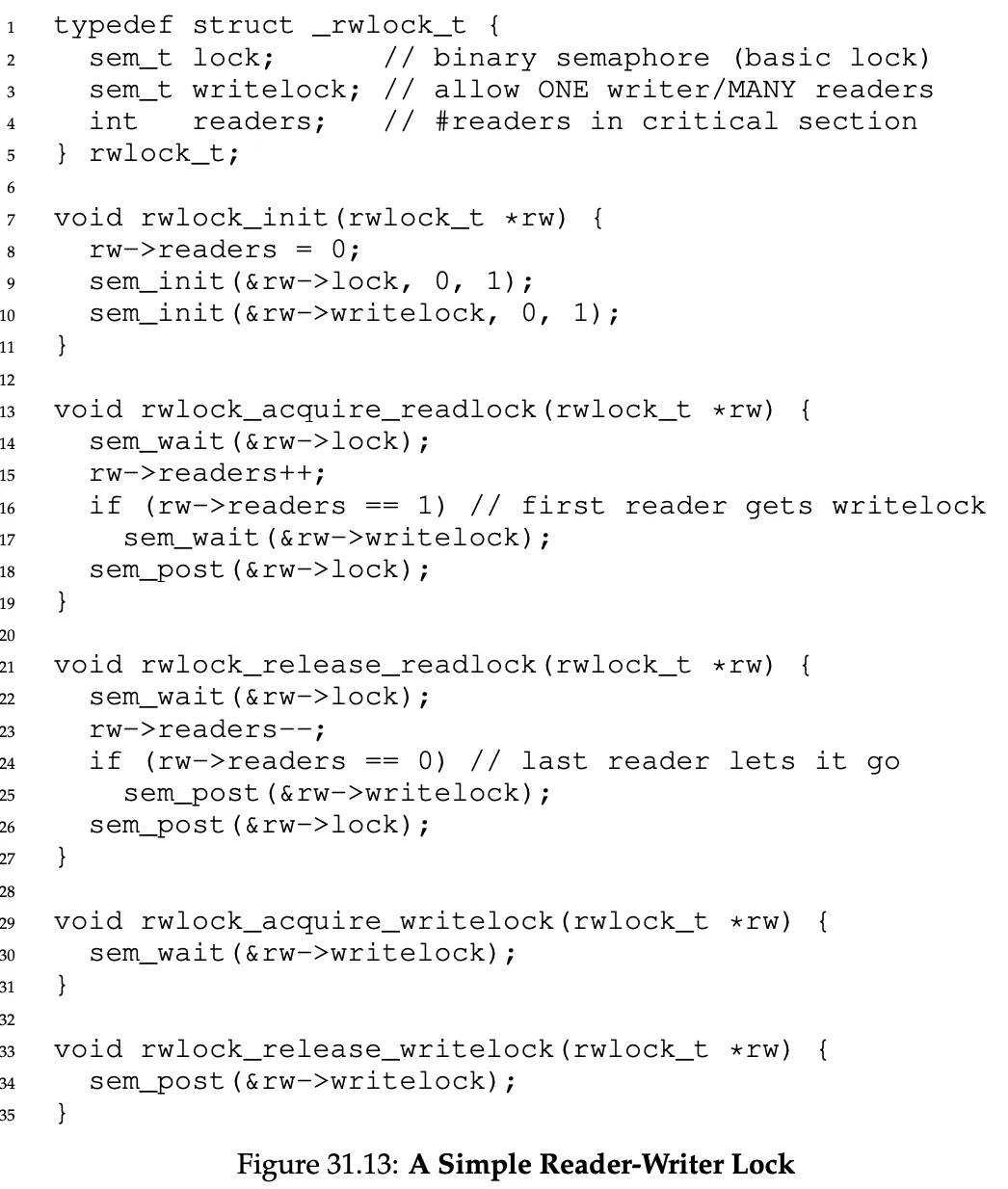

Reader-Writer Locks

If a thread wants to update a data structure, it will acquire the write lock, and then release it when done.

If a reader wants to read, the reader will first acquire lock, then increment the readers varaible to track how many readers are currently inside the data structure. When the first reader acquires the lock, it will also acquire the writelock so that no one can write. More readers will then be able to acquire the read lock too. Writers though, have to wait until all readers have exited the critical section and called sem_post().

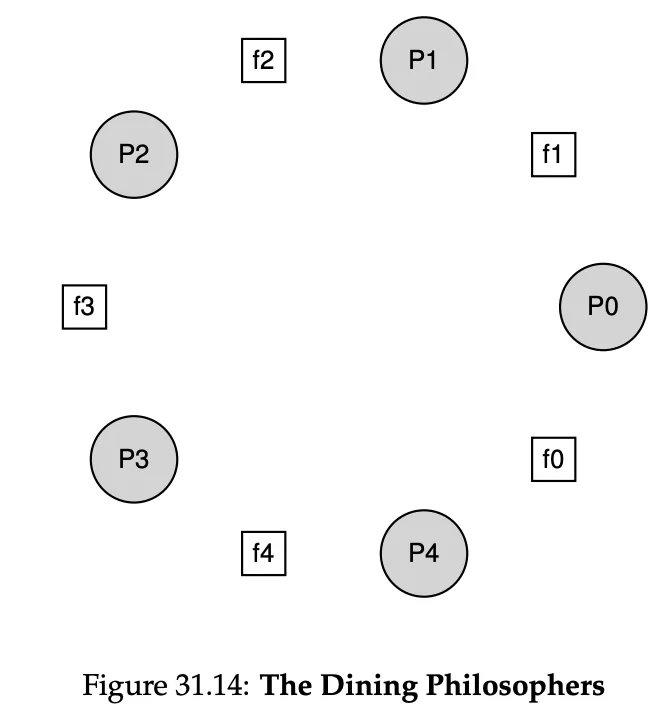

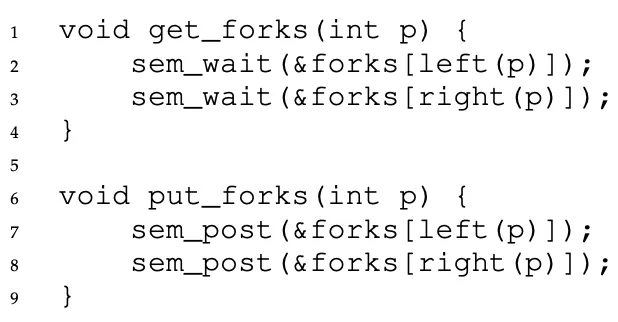

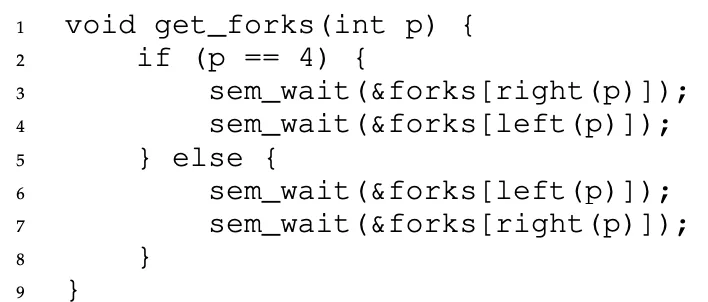

The Dining Philosophers Problem

To eat a philosopher needs both forks, but only one is in between all philosophers.

A simple solution like this doesnt work because of deadlocking. If each philosopher happens to grab the fork on their left before any philosopher can grab the fork on their right, each will be stuck holding one fork and waiting for another, forever.

The simplest way to fix this is this: make one philosopher grab the forks in a different order from the others. That’s it! It breaks the cycle of waiting.

Thread Throttling

A semaphore also allows us to implement easy thread throttling. Let’s say there’s a part of the code that if too many threads access, they will use too much memory and crash the system.

You can just initialize the value of the semaphore to the maximum number of threads allowed. Put sem_wait() and sem_post() around the region, and that’s it!

Semaphore Implementation (the Linux way)